Unlocking Longevity: The Blood Secrets of Centenarians

Discover the key biomarkers that set centenarians apart. Our groundbreaking study reveals how inflammation, glucose, and liver function play a role in exceptional longevity.

Centenarians, once considered rare, have become commonplace. Indeed, they are the fastest-growing demographic group of the world’s population, with numbers roughly doubling every ten years since the 1970s. How long humans can live, and what determines a long and healthy life, have been of interest for as long as we know. Plato and Aristotle discussed and wrote about the ageing process over 2,300 years ago. The pursuit of understanding the secrets behind exceptional longevity isn’t easy, however. It involves unravelling the complex interplay of genetic predisposition and lifestyle factors and how they interact throughout a person’s life.

Unveiling the Biomarkers

Now our recent study, published in GeroScience, has unveiled some common biomarkers, including levels of cholesterol and glucose, in people who live past 90. Nonagenarians and centenarians have long been of intense interest to scientists as they may help us understand how to live longer, and perhaps also how to age in better health. So far, studies of centenarians have often been small scale and focused on a selected group, for example, excluding centenarians who live in care homes. However, our research breaks new ground.

The Largest Study Yet

Ours is the largest study comparing biomarker profiles measured throughout life among exceptionally long-lived people and their shorter-lived peers to date. We compared the biomarker profiles of people who went on to live past the age of 100, and their shorter-lived peers, and investigated the link between the profiles and the chance of becoming a centenarian. Our research included data from 44,000 Swedes who underwent health assessments at ages 64-99 - they were a sample of the so-called Amoris cohort. These participants were then followed through Swedish register data for up to 35 years. Of these people, 1,224, or 2.7%, lived to be 100 years old. The vast majority (85%) of the centenarians were female.

Key Biomarkers

Our study focused on twelve blood-based biomarkers related to inflammation, metabolism, liver and kidney function, as well as potential malnutrition and anaemia. All of these have been associated with ageing or mortality in previous studies. Let’s delve into some of the key findings:

- Uric Acid: A waste product in the body caused by the digestion of certain foods, uric acid was linked to inflammation. Those who made it to their hundredth birthday tended to have lower levels of uric acid from their sixties onwards.

- Glucose and Creatinine: Centenarians had lower levels of glucose and creatinine. These biomarkers are related to metabolic status and kidney function.

- Liver Function Markers: Levels of alanine aminotransferase (Alat), aspartate aminotransferase (Asat), albumin, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase (Alp), and lactate dehydrogenase (LD) were also examined. Those with higher levels of these markers had a lower chance of becoming centenarians.

- Iron and Nutrition: Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC) linked to anaemia, and albumin associated with nutrition, were also part of our investigation.

Implications for Longevity

While these differences are generally quite small, they show that there could be a link between nutrition, metabolic health, and remarkable longevity. Our study provides valuable insights into the intricate web of factors that contribute to living beyond a century. As we continue to unlock the secrets of exceptional longevity, these biomarkers may guide us toward healthier lives and perhaps even the elusive fountain of youth.

Remember, it’s not just about adding years to life; it’s about adding life to years. So, let’s raise a toast to the centenarians and their extraordinary blood – a roadmap to a healthier, longer life.

Disclaimer: This article is intended for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Unlocking Weight Loss Secrets: How Magnesium Can Transform Your Journey

Recent Posts

Abortion Pills Availability: Where to Get Them and What You Need to Know

21st Mar 2024

Link Bеtwееn High-Dеnsity Lipoprotеin (HDL) Cholеstеrol and Dеmеntia Risk

19th Mar 2024

Wegovy: The Revolutionary FDA-Approved Weight Loss Drug Preventing Heart Attacks and Strokes

19th Mar 2024

Depression in Women: A Silent Trigger for Heart Attacks and Strokes

19th Mar 2024

TikTok Trend: Should You Worry About the ‘Mystery Virus 2024’?

19th Mar 2024

Bubonic Plague Resurfaces: An In-depth Analysis of the Recent Death in New Mexico

17th Mar 2024

Unveiling the Power of Bariatric Surgery: A Revolutionary Approach to Obesity and Diabetes Management

17th Mar 2024

Unmasking the Invisible Threat: Microplastics and Heart Disease

14th Mar 2024

Unmasking the Impact of Drug Overdoses on Celebrities’ Social Lives

12th Mar 2024

Unlocking Heart Health: How Daily Walking Can Shield You from Heart Failure

9th Mar 2024

Unlock Pain-Free Living: Yoga for Chronic Low Back Pain

9th Mar 2024

RSV Vaccine Mix-Up: Unraveling the Impact on Pregnant Women and Babies

6th Mar 2024

Unveiling the Truth: Memory Supplements and Alzheimer’s Disease

6th Mar 2024

How To Incorporate Regular Screen Breaks for Optimal Eye Health

5th Mar 2024

Boosting Protection: CDC Urges Older Adults to Receive Updated COVID-19 Vaccine

4th Mar 2024

Norovirus 2024: Cases Surge Across the US – What You Need to Know

4th Mar 2024

CVS and Walgreens to Begin Dispensing Abortion Pills: What You Need to Know

4th Mar 2024

Stress and Cancer: The Silent Culprit Behind Tumor Growth

1st Mar 2024

White-Nose Syndrome in Bats: A Silent Epidemic Threatening Our Winged Night Guardians

1st Mar 2024

Microwave Oven Safety: Choosing the Right Containers for Your Food

28th Feb 2024

Hate Water? Here Are 5 Healthy Alternatives, According to an NFL Sports Dietitian

28th Feb 2024

IVF Tragedy: A Couple’s Unexpected Loss of Embryos Sparks Legal Battle

28th Feb 2024

Bridging the Health Divide: How Dr. Mandy Cohen Plans to Unite America’s Public Health Efforts

28th Feb 2024

Alabama IVF Ruling: Biden’s Health Expert Engages with Families Amidst Legal Battle

28th Feb 2024

Huntington’s Disease: A Comprehensive Guide to Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

27th Feb 2024

Buenos Aires Under Siege: Mosquito Invasion Sparks Dengue Fever Concerns

27th Feb 2024

Florida Measles Outbreak: Surgeon General’s Controversial Stance Sparks Concern

27th Feb 2024

Empowering Strategies for Confronting Cancer: Wisdom from a Two-Time Survivor

27th Feb 2024

IVF Embryo Loss: A Heartbreaking Journey and the Quest for Justice

27th Feb 2024

Florida Measles Outbreak: Cases Spread as State Defies CDC Guidance

26th Feb 2024

Millions Suffer from Long COVID: Why Treatments Remain Elusive

26th Feb 2024

Navigating Breast Cancer in the Era of COVID-19: A Comprehensive Guide

26th Feb 2024

Decoding Esophageal Cancer: From Diagnosis to Treatment

26th Feb 2024

Pistachios: The Tiny Nut with Mighty Health Benefits

26th Feb 2024

Stomach Cancer: Silent Killer Strikes Young – Toby Keith’s Battle and What You Need to Know

24th Feb 2024

Asthma Medication Production Halt Forces Parents to Seek Alternatives: A Growing Concern

24th Feb 2024

Dengue Fever: Unmasking the Mosquito-Borne Threat

24th Feb 2024

Allergic Rhinitis: Unmasking the Springtime Culprit

24th Feb 2024

Worcestershire Royal Hospital Faces Norovirus Outbreak: Visiting Restrictions in Place

24th Feb 2024

Unprecedented Genetic Insights: 275 Million New Variants Discovered in NIH Precision Medicine Data

21st Feb 2024

Heart Disease Diet: Nourishing Your Heart for Lifelong Health

21st Feb 2024

Defending Against Measles, Mumps, and Rubella: The MMR Vaccine Explained

21st Feb 2024

PCOS: Your Ultimate Guide to Diet, Mental Health, and Lifestyle

21st Feb 2024

Unlocking Mental Wellness: The Role of Ketogenic Diets in Psychiatric Health

21st Feb 2024

Unlocking Brain Health: Lifestyle Habits to Safeguard Against Dementia

21st Feb 2024

Unlocking the Niacin Mystery: How This B Vitamin Impacts Heart Health

21st Feb 2024

Nocturia: When the Night Interrupts Your Rest

20th Feb 2024

Unlocking the Brain’s Secrets: A Journey into Cognitive Neuroscience

20th Feb 2024

Unlocking the Genetic Secrets: Key Genes Linked to DNA Damage and Human Health

20th Feb 2024

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD): The Silent Threat to Deer Populations

20th Feb 2024

Menthol in Cigarettes: A Cooling Illusion with Serious Health Implications

20th Feb 2024

Unlocking the Healing Power of Black Seed Oil: From Nigella to Thymoquinone

18th Feb 2024

Sepsis Tragedy: 5-Year-Old Migrant’s Death in Chicago Shelter Sparks Concerns

18th Feb 2024

The Silent Epidemic: Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Its Neurological Toll

18th Feb 2024

Measles Outbreak Alert: Stay Informed and Protected in New South Wales

18th Feb 2024

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma: Unmasking the Silent Threat to Breast Health

17th Feb 2024

Cambodia Reports New Human Cases of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus

16th Feb 2024

Decoding Protein Function: AI, Machine Learning, and the Future of Bioinformatics

16th Feb 2024

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): Unmasking the Silent Struggle of Extreme Mood Shifts

16th Feb 2024

Anxiety Disorders: Unmasking the Silent Struggle

16th Feb 2024

The Dark Side of Zyn: How Social Media’s Influence Is Fueling a Youth Epidemic

14th Feb 2024

SGLT2 Inhibitors: A Breakthrough in Diabetes and Kidney Health

14th Feb 2024

Rosemary Oil for Hair Growth: A Natural Remedy to Combat Hair Loss

14th Feb 2024

Decoding the Heart Symbol: A Journey Through History and Love

14th Feb 2024

Spring Forward, Health Backward: The Impact of Daylight Saving Time on Your Well-Being

14th Feb 2024

Rising Drug Overdose Deaths in Cook County: Urgent Concern for Our Youth

14th Feb 2024

Is Housing Health Care? How State Medicaid Programs Are Redefining Well-Being

14th Feb 2024

Oregon Reports First Human Plague Case in 8 Years: Pet Cat Likely Source

14th Feb 2024

Rio de Janeiro Declares Dengue Public Health Emergency Ahead of Carnival

13th Feb 2024

Grant for South African Seniors: A Lifeline for Ageing Citizens

13th Feb 2024

Coronavirus Outbreak at Attleboro Fire Department: 11 Test Positive

13th Feb 2024

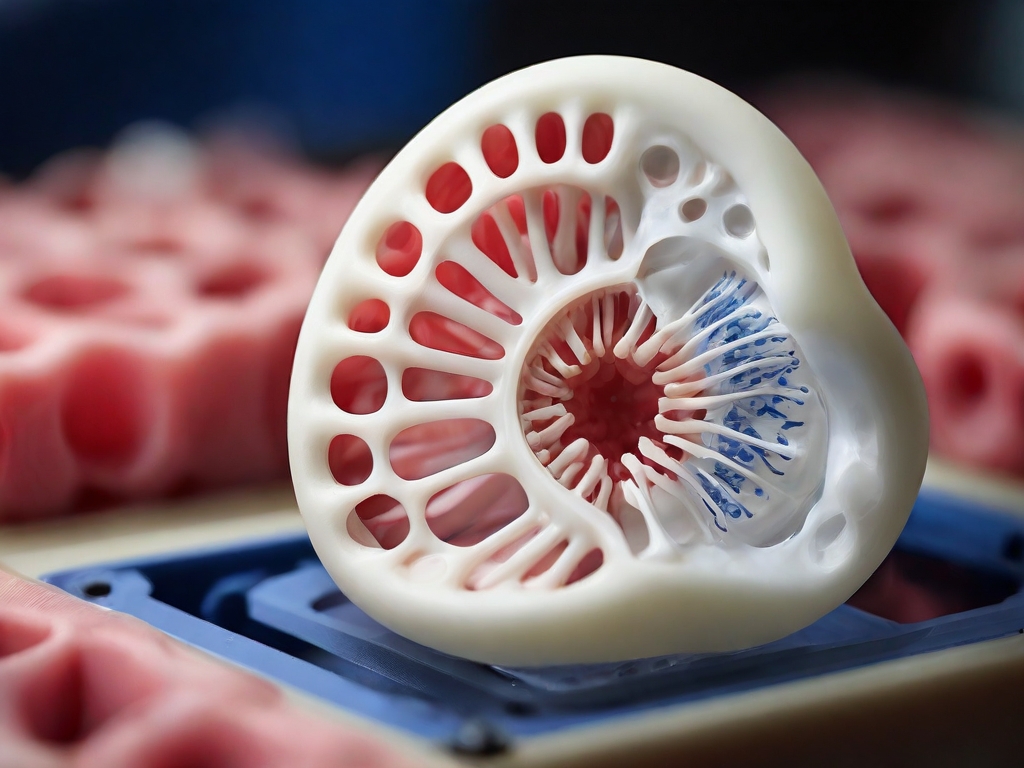

Unlocking the Future: 3D-Printed Artificial Cartilage and Stem Cells

13th Feb 2024

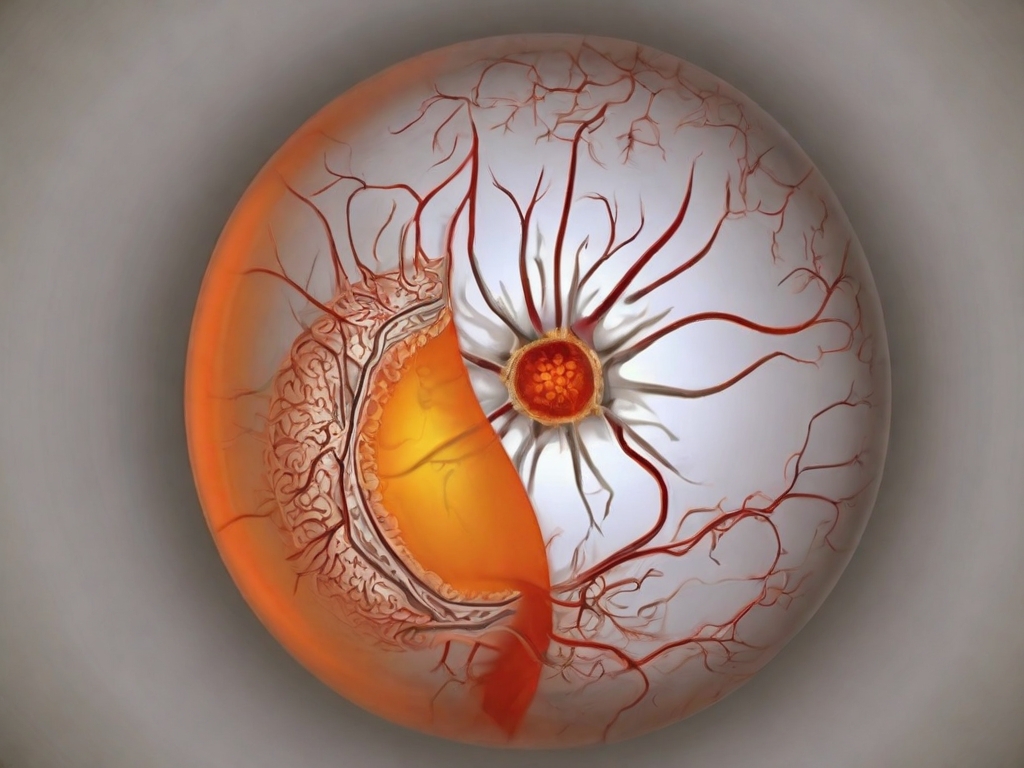

Optic Neuropathy: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

13th Feb 2024

US States Invest Billions in Bold Health Care Experiment: A High-Stakes Gamble

12th Feb 2024

Nicotine and Your Sex Drive: Unraveling the Connection

12th Feb 2024

10 Natural Ways to Lower Your Cholesterol Levels: Evidence-Based Strategies

12th Feb 2024

Pet Poop Can Be Much More Dangerous Than You Might Realize

12th Feb 2024

Uber Eats Super Bowl Ad Sparks Backlash: Food Allergies and the Power of Responsible Advertising

12th Feb 2024

Double Sequential External Defibrillation (DSED): A Breakthrough in Cardiac Arrest Management

12th Feb 2024

The Silent Struggle: How COVID-19 Impacted Mental Health of US College Students

12th Feb 2024

Bladder Cancer: Unraveling the Silent Threat to Your Health

12th Feb 2024

Super Bowl and Prostate Cancer: A Vital Connection

12th Feb 2024

Rare Human Case of Bubonic Plague in Oregon: A Wake-Up Call for Vigilance

12th Feb 2024

Unlock Passion: How Valentine Week Boosts Intimacy and Connection

10th Feb 2024

Cori Broadus: From Stroke Survivor to Health Warrior - A 40-Lb. Transformation

10th Feb 2024

Does Kimchi Actually Promote Weight Loss? A New Study Reveals The Truth

10th Feb 2024

Magic Hangover Pills: Do They Actually Work?

10th Feb 2024

Passive Smoking and Pets: A Silent Threat to Our Furry Companions

10th Feb 2024

The Truth About Jelqing: Risks and Realities of this Controversial Practice

9th Feb 2024

Unlocking Weight Loss Secrets: How Magnesium Can Transform Your Journey

9th Feb 2024

The Blood of Exceptionally Long-Lived People Reveals Key Differences

9th Feb 2024

Opioids and Chronic Pain: An Analytic Review of Clinical Evidence

9th Feb 2024

Blastomycosis: A Rare Fungal Infection Spreads Across Unusual Regions in the US

8th Feb 2024

Breakthrough: New Drug CDDD11-8 Could Halt The Growth of Aggressive Breast Cancer

8th Feb 2024

Apixaban: A Game-Changer in Atrial Fibrillation Treatment

8th Feb 2024

Viagra and Alzheimer’s: A Surprising Link That Could Change Lives

8th Feb 2024

Walking vs. Viagra: Which Is Better for Erectile Dysfunction?

8th Feb 2024

Unlocking the Link Between Depression and Body Temperature: What Science Reveals

7th Feb 2024

Why Aren’t Americans Getting the New COVID-19 Vaccine?

7th Feb 2024

Burgers and Pizzas Could Be Putting You at Risk of Alzheimer’s: What You Need to Know

7th Feb 2024

Plastics Linked to Thousands of Preterm Births in the U.S., Study Finds

7th Feb 2024

Dry Eyes in Winter: Causes, Treatment, and Prevention

7th Feb 2024

The Mind-Skin Connection: How Psychological Stress Impacts Your Dermatology

6th Feb 2024

Fueling Your Run: The Ultimate Runner’s Diet Guide

6th Feb 2024

Frostbite Management: A Comprehensive Guide to Prevention and Treatment

6th Feb 2024

The Unexpected Impact of Troubled Marriages on Your Health

6th Feb 2024

Syphilis: A Preventable and Curable Threat to Public Health

6th Feb 2024

New Estimates Reveal: 1 in 5 People Worldwide Will Develop Cancer

5th Feb 2024

Poonam Pandey’s Fake Death Sparks Debate on Cervical Cancer Awareness: A Closer Look

5th Feb 2024

Pharma Companies Raise Prices on Over 900 Drugs Amid ‘Historic’ Negotiations

5th Feb 2024

Revolutionary Brain Implant for OCD and Epilepsy: Amber Pearson’s Journey

5th Feb 2024

New Drug Shows Promise in Preventing Diabetic Eye and Kidney Complications

5th Feb 2024

Recalled Philips Sleep Apnea Machines Linked to Over 500 Deaths: FDA Issues Urgent Warning

3rd Feb 2024

Medicare Drug Price Negotiations Begin: Key Drugs and Their Impact

3rd Feb 2024

Potassium-enriched salt can Reduce Blood Pressure And Heart Attacks

3rd Feb 2024

Unlocking the Secrets of the Common Cold: A Guide for Parents

3rd Feb 2024

Seattle's Battle with Candida Auris: A Public Health Perspective on the Fungal Outbreak

3rd Feb 2024

Philips Halts U.S. Sales of Sleep Apnea Devices Amid Safety Concerns

30th Jan 2024

Gluten-Free Diet: A Comprehensive Guide on Celiac Disease and Path to Weight Loss

30th Jan 2024

The Nocebo Effect: A Deeper Dive into Medicine's Silent Side Effect

30th Jan 2024

Dangers of 'Gas Station Heroin': FDA's Warning on Tianeptine Supplements

30th Jan 2024

Sleep Patterns Across the U.S.: Discover the States Where People Are Getting the Most Sleep

30th Jan 2024

The Mental Health Crisis Among Youth

29th Jan 2024

Unlocking the Secrets of Sperm Production and Regeneration: A Deep Dive into Male Fertility

29th Jan 2024

COVID-19 and Newborns: Unvaccinated Parents and the Risk of Respiratory Distress

29th Jan 2024

CDC's Urgent Alert: Rising Measles Cases Put Health Care Workers on High Alert

29th Jan 2024

Levemir Discontinuation: A Blow to Diabetes Patients

29th Jan 2024

Lipids: The Unsung Heroes of Health

27th Jan 2024

Navigating the Journey of Smoking Cessation: The Role of Drinks and Nicotine

27th Jan 2024

The Impact of Diet on Ageing: Foods That Accelerate the Ageing Process

27th Jan 2024

Avian Influenza Outbreak in California: A Comprehensive Report

27th Jan 2024

Unveiling the Secrets of Pine Nuts: Health Benefits, Recipes, and More

27th Jan 2024

Exercise: Harnessing the Power of Physical Activity to Manage Menopause Symptoms

26th Jan 2024

Bleach: The Unsung Hero in the Fight Against Bacteria

26th Jan 2024

Home Remedies for Common Ailments: A Scientific Perspective

26th Jan 2024

Chili Peppers: Unleashing the Heat for Pain Management

26th Jan 2024

Uncoated Aspirin: A Natural, Unexpected Acne Treatment

26th Jan 2024

The Hidden Dangers of Snow Shoveling: A Health Perspective

26th Jan 2024

The Health Consequences of Sports Fandom: A Detailed Exploration

25th Jan 2024

Embracing Ayurveda for Kidney Health: Natural Ways to Strengthen Your Kidneys

13th Jan 2024

Mastering Body Recomposition: Building Muscle and Losing Fat with Protein-Rich Meals

13th Jan 2024

Unveiling Magnesium: The Essential Mineral Powering Our Bodies

13th Jan 2024

The Emergence of Weight Loss Drugs in 2024: Exploring The Surge in Market Demand

8th Jan 2024

Unraveling Nutrient Intake Mechanisms and Amino Acid Strategies in Mouse Epiblast Development

3rd Jan 2024

The Role of 3D Chromatin Architecture in Disease Development

3rd Jan 2024

Unravеling thе Link Bеtwееn High-Dеnsity Lipoprotеin (HDL) Cholеstеrol and Dеmеntia Risk

1st Jan 2024

Top 20 Health Questions Answered for 2024

1st Jan 2024